Clan and Conflict in

by Ahren Schaefer, Andrew Black

Terrorism Monitor Volume: 9 Issue: 40

November 4, 2011

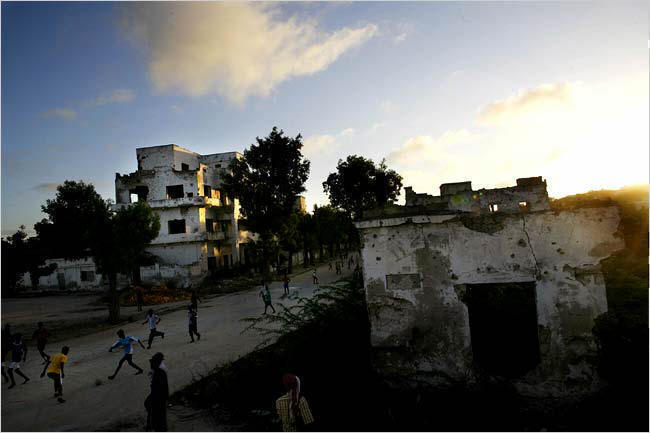

Islamic Courts senior consultative leader Sheik Hassan Dahir Aweys (L) speaks with Sheik Sharif Ahmed, senior Islamic Courts leader, at a cafe in Somalia`s capital Mogadishu airport, November 30, 2006

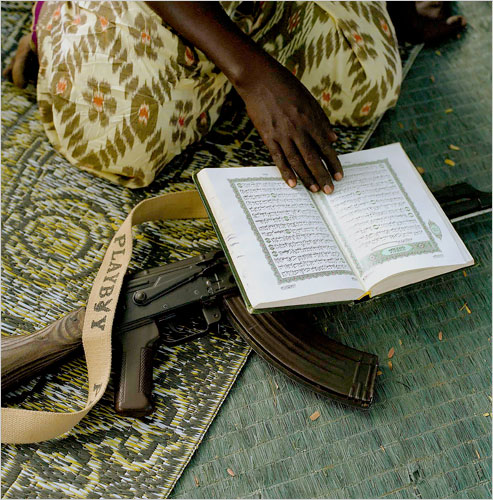

Clan identity and Islam are central pillars of Somali society, with clan dynamics and inter-clan rivalries magnified by decades of state collapse. Al-Shabaab - the dominant Islamist militia controlling much of southern and central Somalia - claims to �transcend clan politics,� yet reality on the ground belies this claim, revealing that al-Shabaab seeks to manipulate local clan alliances and remains deeply influenced by clan politics. This analysis shows that despite al-Shabaab`s hard-line Islamist identity and pro-al-Qaeda rhetoric, many aspects of the group`s past and current behavior remain deeply rooted in Somalia`s local dynamics. Moreover, clan rules apply even to Somalia`s most feared Islamists.,

Somalia - All Politics are Local

Clan and sub-clan structures are central to Somali identity. From a young age, children are traditionally taught to memorize and recite their clan-based kinship genealogy, sometimes naming twenty or even thirty generations of their patrilineal ancestors. [1] When the Siad Barre regime collapsed in 1991 and with it the presence of centralized Mogadishu-based governance, inter-clan violence and power rivalries spiked as clan structures and identities filled the governance void. The destructiveness of this process contributed to a paradoxical perception of clans that remains palpable today. Though many Somalis often self-identify based on clan, they nevertheless blame �clannish� behavior for the fractionalization, violence, and the destruction of Somali stability. [2]

Nevertheless, Somali society continues to be defined by clan identities, and clan rivalries frame the balance of power across

This complex and interlocking system establishes the rules by which Somali politicians, warlords, and even terrorists must abide. As al-Shabaab has developed in recent years and sought to balance domestic priorities with international jihadi ideals, the role of clan has continued to plague and shape the organization.

Al-Shabaab - Avoiding the Stigma of �Clannish Behavior�

Al-Shabaab rose to prominence in 2006 as a militia subordinate to the Islamic Courts Union (ICU) and was typically criticized as being a Hawiye militia. [4] The Habr Gedir/Ayr sub-clan factions of the powerful Hawiye clan were noted as being particularly influential within the Islamic Courts at the time. Under the leadership of Aden Hashi Ayro, al-Shabaab became known for its Takfiri-Salafi worldview and links with al-Qaeda. [5]

With the dissolution of the ICU following the invasion of Somalia by the locally-reviled Ethiopian military, al-Shabaab arose as the most competent and capable resistance force against the Ethiopian occupation, even drawing on members of Somalia`s minority clans (�looma ooyan�) and building a multi-clan leadership structure (Suna Times, November 10, 2010). [6] Dr. Andre Le Sage notes that Ahmad Abdi Godane, Fu`ad Shongole, and Ibrahim Haji Jama, along with al-Shabaab`s foreign fighter cadre, are the more radical leaders favoring the ideology of al-Qaeda`s global jihad. In contrast, other Shabaab leaders and many of the groups rank-and-file have little loyalty to this trans-national cause. [7]

Al-Shabaab`s protracted campaign against the deeply resented Ethiopians allowed the group`s more jihad-oriented leadership to equate their radical agenda with nationalist sentiment and gain more cross-clan support than would have been possible absent a �common enemy.� [8] In an effort to galvanize cross-clan support, al-Shabaab highlighted its Islamist and nationalist credentials, and in the face of the Ethiopian occupation, al-Shabaab succeeded in establishing hegemony in south-central

Since the Ethiopian withdrawal from

However utilitarian this narrative may seem, al-Shabaab`s clannish behaviors in Somalia belie the universality of this narrative, and show the organization to be fighting clan-based struggles internally and with other key players in Somalia.

The Rise of al-Shabaab�Still Fighting Clan Battles

Al-Shabaab`s strategy and its inability to avoid clan influence has affected the way the group projects force, recruits fighters, and influences the Somali population. In these ways, al-Shabaab has evolved drastically over the past five years. Initially a relatively small militia, al-Shabaab gained local support as the only effective fighting force against the Ethiopian intervention in

While al-Shabaab`s multi-clan leadership has been beneficial to the movement, disagreements between key leaders like Amir Ahmad Abdi Godane �Abu Zubayr� (Isaaq/Arap) from the north and Commander Mukhtar Robow �Abu Mansur� (Rahanweyn/ Mirifle/Laysan) have created friction within the group. Al-Shabaab`s Ramadan offensive in 2010 ended with numerous reports in the Somali press of a major leadership rift within al-Shabaab - a reaction to the failed offensive and the grievances of clan constituents. Specifically, Mukhtar Robow allegedly withdrew his Rahanweyn forces from

Al-Shabaab`s cross-clan narrative helps to mask the relative weakness of its leaders, Amir Ahmed Abdi Godane and Ibrahim Haji Jama al-Afghani, both of whom are members of the Isaaq clan of Somaliland, an autonomous region far from al-Shabaab`s normal region of operations in southern Somalia. Consequently, these leaders lack a natural power base in areas of southern

Fighting Clan Battles

A review of al-Shabaab`s battles in recent years reveals clear clan dynamics. Fighting between al-Shabaab, allied Islamist militia around Mogadishu, and Somalia`s feeble Transitional Federal Government (TFG) surged in May 2009 and again during al-Shabaab`s Ramadan offensive of 2010 (see Terrorism Monitor, October 21, 2010). In both cases, the presence of the roughly 7,000 peacekeepers of the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) prevented al-Shabaab from toppling the TFG. Fighting in central

South of Mogadishu, al-Shabaab has engaged in clan-based fighting to control the strategically important

Emergence of Ahlu Sunna wa`l-Jama`a

Farther north, al-Shabaab has fought against a loosely structured alliance called Ahlu Sunna wa`l-Jama`a (ASWJ). Although nominally a Sufi conglomeration that armed itself in reaction to al-Shabaab`s desecration of Sufi tombs, ASWJ is largely formed along clan lines in the Galguduud, Hiraan and Gedo regions. ASWJ`s strength stems in part from clan-based support, as elements of the Habir Gedir, Dir, and Marehan sub-clans elected to support ASWJ against al-Shabaab (Shabelle Media Network, January 24; Garowe Online, January 25). [16]

Even beyond southern and central

Even recruitment of foreign fighters - at least those of ethnic Somali origin - may have a clan-based component. A March 2010 report by the United Nations noted that more than half of the initial twenty Somalis who left

It is worth noting the unique challenges clan dynamics impose on al-Shabaab as the organization attempts to recruit foreign fighters. Somalia`s strong clan identities, prevailing instability, and wariness of foreign influence make the country inhospitable to individuals of non-Somali origin. [21] Al-Qaeda learned this lesson in the early 1990s, when Osama bin Laden - then based in

Conclusion: Clan Influence and Countering al-Shabaab

The foregoing has shown the inconsistencies between al-Shabaab`s narrative and the group`s clannish behaviors. Though attempting to position itself as transcending clan rivalries in pursuit of a pan-Somali and Islamist agenda, evidence shows al-Shabaab to be embroiled in local clan-based disputes.

For policy-makers, this presents multiple strategic opportunities. In terms of al-Shabaab`s placement as an adherent to al-Qaeda`s worldview, the organization is caught between proving its Salafi-Jihadi credentials to core al-Qaeda and affiliated movements while attempting to establish power among a Somali population that focuses internally on parochial clan interests. Any disruption to this careful balance risks either undermining al-Shabaab`s carefully built power-base in Somalia or losing the support of international Salafi-Jihadis.

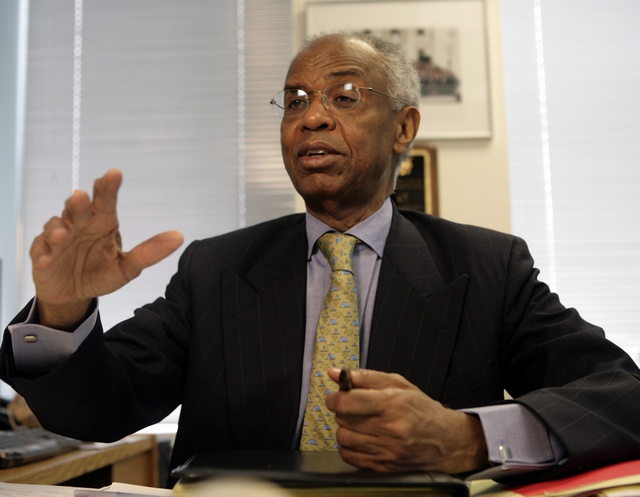

Partly in recognition of this opportunity, Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Johnnie Carson announced a new �Dual Track� policy for Somalia in October 2010 designed to support not only the TFG, but also promote local civil society and stability efforts across Somalia. [23] Success for this dual track initiative would almost certainly require greater clan involvement and therefore would challenge al-Shabaab`s local power-base and potentially disrupt the group`s internal leadership balance. For the strategy to succeed, Somalia`s TFG will need to foster clan alliances, both militarily and politically, and show greater strength independence from AMISOM (Reuters, August 6). Some experts point to nascent indicators of an Iraqi-style �Awakening movement,� however, such efforts have not yet materialized in a systemic manner (East African, January 24). New clan-based groups opposed to al-Shabaab have emerged, but their sustainability remains uncertain. [24]

This review of al-Shabaab`s evolution and Somalia`s ongoing conflict leaves little doubt that clan politics continue to influence al-Shabaab to a substantial degree. Looking ahead, the group`s ability to forge and maintain clan alliances will be fundamental to al-Shabaab`s trajectory and viability in the long term.

Ahren Schaefer is a Foreign Affairs Research Analyst at the U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Intelligence and Research.

Andrew Black is the CEO of Navanti Group, LLC.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the

Footnotes:

1. �Somali Social Structure: A System of Kinship and Clan,� Library of Congress, July 2010,

p. 2.

2. Andrea Levy, �Looking Toward the Future: Citizen Attitudes about Peace, Governance and the Future of Somalia,� National Democratic Institute, December 6, 2010; �Somali Social Structure,� op cit, p. 4.

3. Matt Bryden, �New Hope for

4. Andrew McGregor, Who`s Who in the Somali Insurgency: A Reference Guide, Jamestown Foundation, Washington D.C., September 2009, p. 8.

5. For a description of this term, see: Quintan Wiktorowicz,� Anatomy of the Salafi Movement,� Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 29, 2006, pp. 207-239.

6. See: Angel Rabasa, �Radical Islam in East Africa,� RAND, Project Air Force, 2009; �Somalia`s Divided Islamists,� ICG Africa Briefing 74, May 18, 2010, p. 6; Report of the Monitoring Group on Somalia Pursuant to Security Council Resolution 1853. United Nations Security Council. March 10, 2010, p. 14.

For information about Somalia`s minority clans, refer to: Report on Minority Groups in Somalia, Joint British, Danish and Dutch Fact-Finding Mission to Nairobi, Kenya, September 17-24, 2000, http://www.somraf.org/research%20Matrerials/joint%20british%20danish%20dutch%20fact%20finding%20mission%20in%20Nairobi%20-%202001.pdf;

7. Andre Le Sage, Somalia`s Endless Transition: Breaking the Deadlock, Strategic Forum 257, Institute for National Strategic Studies, National Defense University, June 2010, http://www.ndu.edu/inss/docuploaded/SF%20257.pdf .

8. David Shinn, �Somalia`s New Government and the Challenge of al-Shabaab,� CTC Sentinel, March 2009.

9. Ken Menkhaus, �Violent Islamic Extremism: Al-Shabaab Recruitment in

10. �Somalia`s Divided Islamists,� op cit. ; Le Sage, op cit; Report of the United Nations Monitoring Group on Somalia, op cit.; �Somalia`s Islamists,� ICG Africa Report 100, December 12, 2005, p. 14.

11. McGregor, op cit, p. 15; �Somalia`s Divided Islamists,� op cit, pp. 5-7, 11; Report of the Monitoring Group on Somalia 2010, p. 27.

12. Le Sage, op cit.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid; Report of the Monitoring Group on Somalia 2010, pp. 11, 17.

15. �Somalia`s Divided Islamists,� op cit, p. 9; Le Sage, op cit.

16. Report of the Monitoring Group on Somalia 2010, p. 11; Abdulahi Hassan, �Inside Look at the Fighting Between al-Shabaab and Ahlu-Sunna wal-Jama,� CTC Sentinel, March 2009.

17. See Andrew McGregor, �Puntland`s Shaykh Muhammad Atam: Clan Militia Leader or al-Qaeda Terrorist?� Militant Leadership Monitor, September 29, 2010, http://mlm.jamestown.org/single/?tx_ttnews%5bswords%5d=8fd5893941d69d0be3f378576261ae3e&tx_ttnews%5bany_of_the_words%5d=atam&tx_ttnews%5btt_news%5d=36982&tx_ttnews%5bbackPid%5d=539&cHash=fa328428d5b609a8f08dc9e4994e3535 .

18. Report of the Monitoring Group on Somalia 2010, pp. 16, 20-22, 45; Somalia Online, �Atom denies Al-Shabaab links,� May 18, 2011.

19. �Somalia`s Divided Islamists,� op cit, p. 11; Matt Bryden.

20. Report of the Monitoring Group on Somalia 2010, p. 33.

21. �Al Qaeda in Yemen and Somalia: A Ticking Time Bomb,� Report to the Committee on Foreign Relations, United States Senate, January 21, 2010, pp. 4, 14.; Andrew Black, �Recruitment Drive: Can Somalia Attract Foreign Fighters?� Jane`s Intelligence Review, 19(6), 2007, pp. 12�17.

22. �Al-Qaeda`s Misadventures in the Horn of Africa,� op cit.

23.

24. Le Sage, op cit.

|

|

Sawirro Somaliya  |

|

GOVERNANCE

The Scourge and Hope of Somalia A New Book By Ismail Ali Ismail  Which Way to the Sea, Please? By Nuraddin Farah Dhulkii Burcad-Badeedda .jpg) Budhcad Badeed Weli Qiil ma Leeyahay?  SYL LETTERS By A S Faamo |

|

|

© Copyright BiyoKulule Online All rights reserved�

Contact us [email protected] or [email protected] |

.jpg)