�Oil Sheikhs� Imagination Runs Deep in the Horn

Biyokulule Online

August 27, 2011

For the last few decades, Somalis were captivated by the imagination of having riches that are not there. Somalis believe that their country is sitting on top of billions of barrels of crude oil. Their imaginations have therefore no boundaries.

In December 2008, Liban Bogor who is the nephew of former President of Puntland Regional Administration told a reporter that in 20 years Puntland will look like

Puntlanders therefore rightly dream about the �black gold�; and if the current Puntland Administration discovers such manna, it will surely alleviate the scourges of poverty and famine. Puntlanders will surely interpret the dream of oil as free healthcare, education, and jobs.

Although at times of hardship a leader with an enormous imaginative power is needed in order to find solutions, it is not a wise idea to make poor Puntlanders excited and stoke their imaginations, telling them that they will soon be �oil sheikhs� � while �it is far from certain that there is any oil at all�.

How about if the words of our imaginative leaders results in many Puntlanders dream of the impossible, or even imagine of seceding from the rest of

A superstitious saying states that if you see oil in your dreams you will quarrel with others. Therefore, is it possible, in the near future, to see oil imaginations make

Upstream

August 26, 2011

Breakaway state tries to surmount problems bringing in E&P business as it petitions UN for recognition

SOMALILAND Minister for Foreign Affairs & International Co-operation Mohamed Omar this week convened a meeting with

Omar noted that nearby

Hargeisa last month attended South Sudan`s independence celebrations in Juba and will formally seek recognition as a sovereign state in the United Nations Security Council - �but we have no intention of making trouble�, said Omar.

IN ADDITION to Somali acreage licensed in

Beating competition from the National Oil Company of

� 2011, Upstream.

Horn lines up two wildcats for Puntland

Upstream

August 26, 2011

HORN Petroleum will start drilling the first of two planned wildcats onshore Puntland, the semi-autonomous

The initial well, Shabeel-1, is the first to be drilled in the region for two decades and the partners claim the operation enjoys the full support and protection of the �key clans� of Dharoor.

Horn plans to target two prospects together estimated to hold a potential 675 million barrels of oil, of which 300 million barrels is ascribed to Shabeel-1.

Partial relinquishments in both the

� 2011, Upstream.

Oil and Troubled Waters

Derek Brower

Prospect Magazine

December 17, 2008

Plagued by piracy, Islamic extremism and endless civil war, surely it can`t get any worse for

In 20 years it will look like

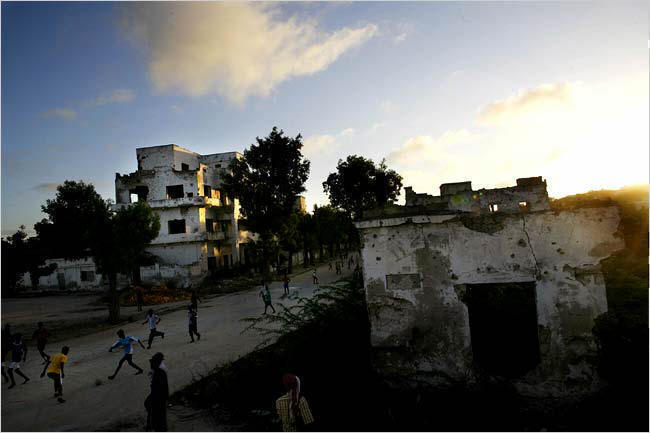

Bosaso is a hardscrabble Somalian town. The economy, such as it is, depends on the export of goats across the Gulf of Aden to

When our plane touched down in the town after a five-hour flight from

Bosaso lies in the north of Puntland, a semi-autonomous province in northeast

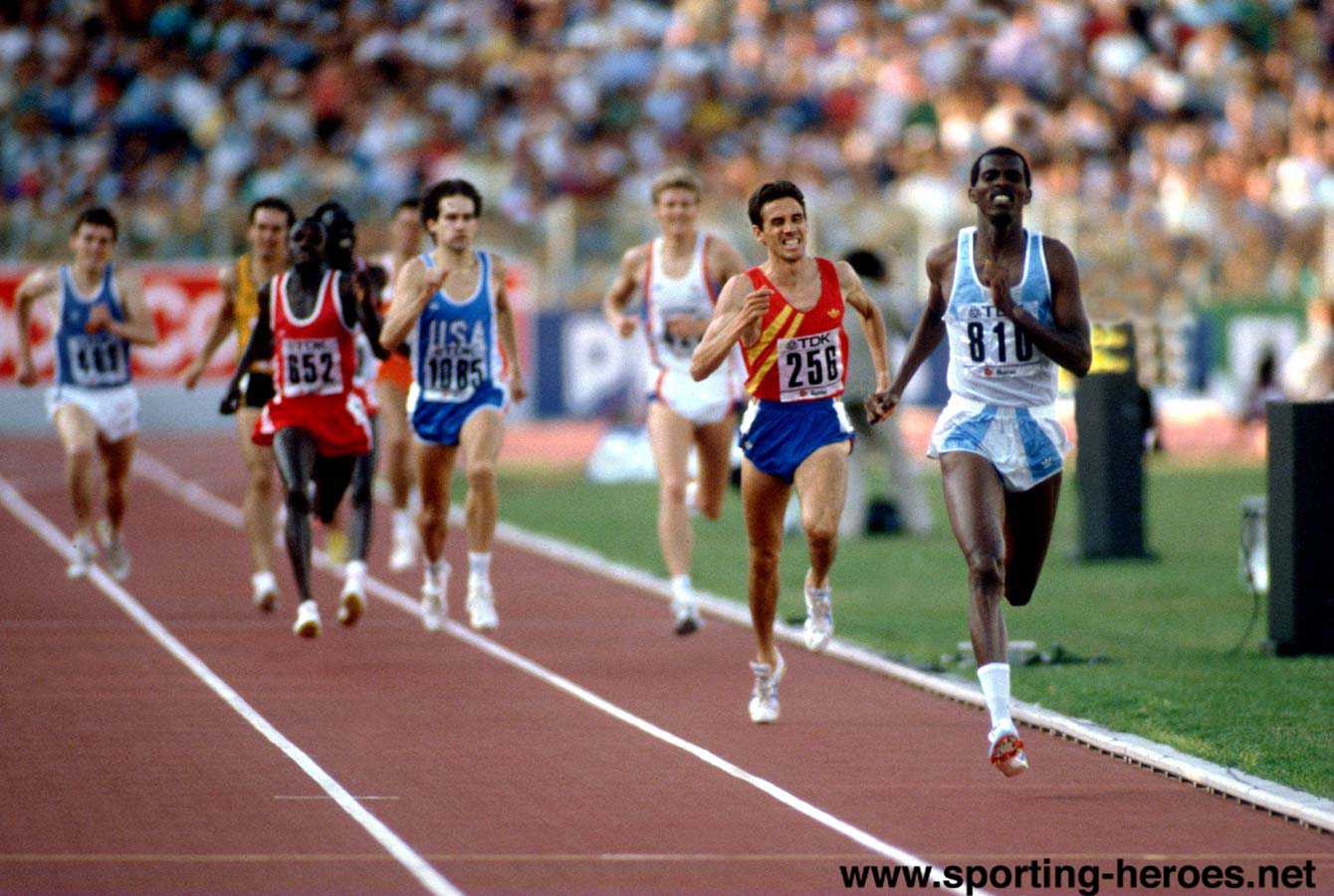

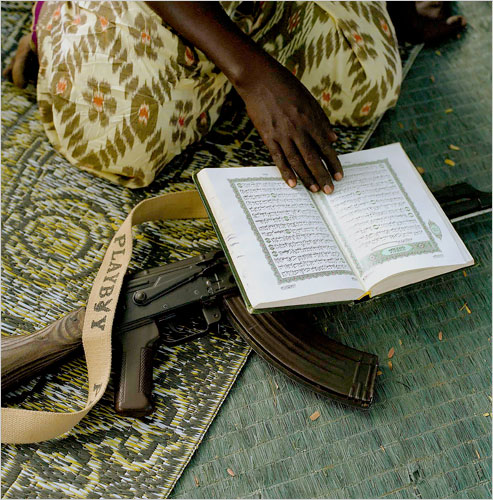

Despite the piracy, the anarchy that afflicts the south of Somalia feels a long way from Puntland, although Ethiopia`s plans to withdraw its army from Somalia could, some analysts say, leave the entire country on the brink. Sharia law is alien to its clan-dominated society, which locals say is the reason for the province`s relative peace. Some pirates claim their booming business is a model of inter-clan co-operation. And, for now, Puntland is on the right side of the power battle further south. The president of the Ethiopian-backed transitional Somali government, Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed, is a former president of the province and Puntlander fighters surround him in

But violence isn`t far beneath the surface. The offshore piracy is just the most visible symptom of Puntland`s-and Somalia`s-dysfunction. Grenade attacks and gunfights erupted in Bosaso in 2008 and local reports say a state of emergency was recently imposed across the region. Somaliland, a neighbouring part of

All this makes Bogor`s dream of Puntland as the new Dubai hard to picture. Yet there`s a reason for his optimism: oil. Until recently, Bogor was a director of a small Australian oil company called Range Resources, which believes it is sitting on up to 10bn barrels of oil in the province. It wouldn`t turn

But in reality, Range`s involvement in Somalia threatens to pour petrol on an already inflamed situation. It is far from certain that there is any oil at all. Range isn`t the first company to explore in Puntland. The

Puntland shouldn`t have to wait long to find out which view is correct. Range and its more experienced Canadian partner, Africa Oil Corp, say they will drill their first well, in the Dharoor block, in the next three months. If Range finds oil, its share price on London`s Alternative Investment Market, the junior stock exchange, will soar. The directors say they hope to be �cleaned out�-or taken over-by a larger firm. �We`re not oilmen,� Peter Landau, one of them, told me. They are corporate adventurers: the kind of men who enjoy travelling in convoy under armed guard and aren`t afraid to get their hands dirty to cut a deal.

Puntland is already counting on the oil. The provincial government`s five-year development plan states, erroneously, that �500m barrels of recoverable oil have been discovered so far.� When I and a handful of other journalists visited the place, at Range`s invitation (a PR effort designed to drum up shareholder interest), the provincial president and his ministers seemed to think that the company could make Puntland rich beyond the dreams of the most qat-crazed pirate. In their minds, the days of electricity blackouts in the president`s office are over.

Oil would, of course, be a more mixed blessing for Puntland as a whole. When I asked the president, Mohamoud Musa Hirsi, what he would do with revenue from future oil production, he replied: �Spend it on security.� That is because oil will very likely lead to another civil war. Hirsi and others in the government fear both Somaliland, whose territorial claims extend to land on which Range plans to drill, and the transitional federal government (TFG) in

Despite his own background in Puntland, the TFG`s president Yusuf says that natural resources belong to Somalia as a whole. He has even put out feelers to Asian and middle eastern firms to help him form a national Somali oil company. But for the time being, the TFG does not have the means to enforce its will in Puntland, so Range`s contract remains valid.

It is rumoured that Chinese or other Asian investors may help fund an invasion of Puntland, should oil be found. Some investors have already negotiated with neighbouring

Even before the first well has been sunk, violence had broken out. The Warsangeli, a clan in the Sanaag region that object to Range exploring in their territory, confronted geologists sent to take samples. Garowe Online, a website run by disgruntled emigre Puntlanders, reported that in March 2006 ten clan members were killed during a gunfight involving militiamen defending the oil seekers. Those militiamen, says a local source, work for

Range`s promotional YouTube video has been reproduced and mocked by opponents with the title �Oil Thugs� and the introductory line, �Mate, here`s a candy, now give me your oil.� They claim that many members of the provincial government (including the president) are shareholders in either Range or Consort, a company with opaque origins that held the original licence to develop the province`s mineral resources. Range`s exploration contract included a bonus payment of $20m to be made to Consort after it had drilled its fourth well. (Range has certainly ingratiated itself with Puntland`s administration. It is paying to build a new airport in Bosaso, for example. But it denies that Bogor or any government ministers are shareholders in Consort, and says Range`s shareholding structure was checked by the London stock exchange at the time of listing.)

President Hirsi told me that Range had helped to draw up the laws governing its own operations there. Any company that wanted to explore in the region, he added, must speak to Range first. And Range also employs its own private security men to protect its executives in the turbulent region of Puntland; which, Garowe Online claims, amounts to the company`s own private army.

In the context of the new scramble for Africa`s resources, there`s nothing unusual about Range. There are plenty of small companies raising money to invest in chaotic states. Ironically, this is one consequence of the corporate do-gooding that has tied the hands of western oil majors in

Range`s directors make no pretence. They want to find oil and sell themselves to a larger company, allowing them to retire as millionaires. In the meantime, they`re risking everything on a drilling programme that could find oil-or disappoint people in one of the most impoverished corners of

� Copyright 2008. Prospect Magazine.

The best thing that could happen to the country is if no oil is found

Xan Rice in Sao Tome

The Guardian

July 14, 2008

Children outside their shack in the tropical forest in Riba Mato, a suburb of

Bribery, bullying and bad deals shatter poor nations dreams of petroleum boom

Luis Prazeres was the first native-born airline captain in Sao Tome and Principe, and the country`s first minister of natural resources. He knew a lot about flying and nothing about oil. But neither did anyone else in the tiny African island nation, which had just been told it was on the verge of a petroleum boom.

�There were all these foreign companies telling us that we had huge oil reserves, and bringing us agreements to sign,� said Prazeres, who took up his minister`s post in 1999. �Nobody here understood how complex it was.�

Other governments are now finding themselves in similar situations. Rising oil prices have led to a surge in exploration in countries with little or no petroleum experience. Hopes of petrodollar bonanzas have already been raised in

Yet Sao Tome`s bitter experience should serve as a cautionary tale. In the decade since a little known Texas oil firm wandered into government offices with an audacious plan, the 160,000 inhabitants of the lush, somnolent islands have seen dreams of their country becoming the next Brunei or Kuwait melt away in the equatorial sun.

Their leaders have signed some of the most lopsided petroleum contracts in history. Bribes have allegedly been offered and pocketed. Regional bullies have muscled in, and in May the government fell to a no-confidence vote. �We have already seen everything that goes with an oil boom,� said Rafael Branco, the newly appointed prime minister. �Everything, except a single drop of oil.�

Offshore reserves

The twin islands of

In 1997, a tiny Houston-based company called Environmental Remediation Holding Corporation (ERHC), which had no history of oil finds or production, decided

When Sao Tome`s current president, Fradique de Menezes, was elected in 2001 he threatened to have ERHC`s contract torn up, but by then the US company had been bought by Chrome, a Nigerian firm headed by a businessman with strong ties to Nigeria`s ruling regime. Though the contract would be renegotiated twice, pressure from Nigeria ensured ERHC`s deal remained vastly disadvantageous for Sao Tome.

Meanwhile, the potential oil reserves were causing excitement abroad. After the 9/11 attacks, the

Several top

�All people could talk about was oil, oil, oil. The politicians made it sound like it would start flowing tomorrow, and everyone was just sitting back and waiting for the proceeds,� said Arlindo Carvalho, who was oil minister from 2003 to 2005.

The best blocks in the joint Sao Tome-Nigeria oil zone had been put up for auction in 2003. In the first round, only one consortium, led by Chevron and ExxonMobil, emerged with a successful bid. Sao Tome`s share of the fee was $49m - a lot to a tiny country, but far less than expected. Late in 2004, more than two dozen companies competed for the remaining blocks. Many were Nigerian-linked firms with no experience of oil production.

Manipulation

A report by Sao Tome`s attorney general a year later concluded the auction had lacked transparency, was subject to �serious procedural deficiencies and political manipulation�, and had resulted in winning bids from unqualified firms. ERHC`s preferential rights had discouraged the more reputable companies from bidding, and cost Sao Tome up to $60m in fees, it said.

Even more damning, to Sao Tomeans, were allegations in the report that their politicians had been bribed. One of the president`s top advisers was revealed to own a stake in ERHC, while a company controlled by Menezes was found to have accepted $100,000 from Chrome. Menezes and Chrome said the payment was a legitimate election contribution.

Public anger was followed by disappointment at the oil drilling results. When Chevron tested its deep-water block in 2006, it struck oil but not in commercial quantities. Other companies plan tests next year. The government also intends to sell exploration rights in its exclusive territorial waters in 2009.

Even if commercial quantities of oil are discovered, it will be at least six years before production starts.

�There is a lot of exhaustion with the whole process,� said Paulo Cunha, who managed the

Others are not so certain. There is still very limited oil expertise on the islands. And given the alleged corruption, many local people have serious doubts that oil revenues could be managed properly, regardless of the good laws in place.

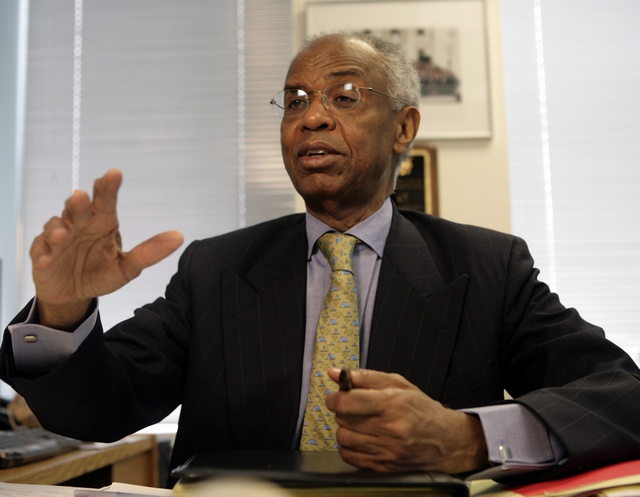

�Sao Tome`s institutions remain among the weakest in Africa,� said Yahya. �The best thing that could happen to the country is if no oil is found.�

� Copyright 2008. The Guardian. All rights reserved.

|

|

Sawirro Somaliya  |

|

GOVERNANCE

The Scourge and Hope of Somalia A New Book By Ismail Ali Ismail  Which Way to the Sea, Please? By Nuraddin Farah Dhulkii Burcad-Badeedda .jpg) Budhcad Badeed Weli Qiil ma Leeyahay?  SYL LETTERS By A S Faamo |

|

|

© Copyright BiyoKulule Online All rights reserved�

Contact us [email protected] or [email protected] |

.jpg)